An interview with Sufi mystic Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee

When you pay attention to what’s happening to the world—the destruction of our air, soil, and water—it is common to want to do something to help the situation. But what if part of the reason that we’re in this perilous ecological situation is our tendency to treat the world as if it’s a problem to be solved?

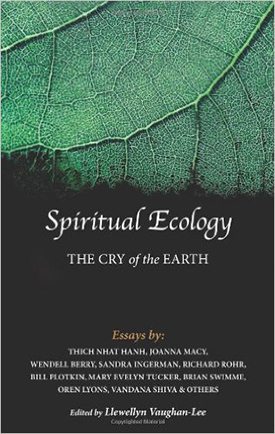

In his book Spiritual Ecology: The Cry of the Earth, Sufi mystic Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee writes that much of our understanding of the ecological crisis belongs to “the mindset that has caused the imbalance.” To restore balance we need a shift in consciousness and then action that embodies this shift. In answer to the question, “What can we do?” Vaughan-Lee has recently written a follow-up book, Spiritual Ecology: 10 Practices to Reawaken the Sacred in Everyday Life, which explores practices that can help us to experience a deep, lived connection with the planet. And while this is an urgently important task, it will not be achieved by a quick fix of technology and policy, but rather through multigenerational spiritual work.

Vaughan-Lee is a lineage holder in the Naqshbandiyya-Mujaddidiyya Sufi Order and the founder of The Golden Sufi Center. In addition to Spiritual Ecology, he is the author of Fragments of a Love Story, Darkening of the Light, and other books. We corresponded with him recently about the challenge of bringing humanity back into harmony with the life-systems that support us.

In Spiritual Ecology: The Cry of the Earth, many of the contributors suggest that ecological crisis is rooted in urgent spiritual and moral questions. Can you give me some examples of these spiritual questions?

Today we are faced with an ecological crisis of rising sea levels, polluted air, toxic oceans, and a mass extinction of species. One response to this crisis is “greening the economy,” which looks to technological innovation to ensure sustainable development without further degrading the environment. But in recent years there has been a deeper questioning that suggests that the ecological crisis requires a spiritual and moral response. This has been forcefully articulated in Pope Francis’s encyclical, Laudato Si’: On Care for our Common Home, which asks us to look at the spiritual and moral issues underlying the unprecedented destruction of ecosystems we are inflicting upon the Earth.

Native American Faithkeeper Chief Oren Lyons offers another example of a spiritual response to our ecological crisis when he describes the spiritual laws of nature and the need for thanksgiving. The Zen monk Thich Nhat Hanh sees our present ecological crisis as “bells of mindfulness” to wake up and change our consciousness in order to be aware of what is happening to the Earth. He says that we have to “fall in love” with the Earth, echoing the poet Wendell Berry who says that the world “can only be redeemed by love.” While the Buddhist activist Joanna Macy speaks of how our hearts can be cracked open by the grief at what we are doing the world and says, “as your heart breaks open there will be room for the world to heal.”

Native American Faithkeeper Chief Oren Lyons offers another example of a spiritual response to our ecological crisis when he describes the spiritual laws of nature and the need for thanksgiving. The Zen monk Thich Nhat Hanh sees our present ecological crisis as “bells of mindfulness” to wake up and change our consciousness in order to be aware of what is happening to the Earth. He says that we have to “fall in love” with the Earth, echoing the poet Wendell Berry who says that the world “can only be redeemed by love.” While the Buddhist activist Joanna Macy speaks of how our hearts can be cracked open by the grief at what we are doing the world and says, “as your heart breaks open there will be room for the world to heal.”

All these voices speak to the need to search beyond a merely physical or technological response to the present crisis and ask the deeper spiritual questions, which they believe are at the root of our present imbalance.

These examples suggest that spiritual responses to the ecological crisis have an important role to play in healing the Earth moving forward, but Spiritual Ecology also suggests that it was a spiritual crisis that has led us to our current situation. Can you comment on this?

There is an argument that the origin of our present ecological crisis can be traced back to the Age of Enlightenment, when the emerging Newtonian model saw the physical world as unfeeling matter, a clockwork mechanism that we should understand and control. This consciousness may have given us the fruits of science and technology, but its cost was to create a mindset of separation that cut off humanity from the awareness of our natural interrelatedness with our world.

But perhaps we can look even deeper: How have we lost and entirely forgotten any spiritual relationship to life and the planet, a central reality to other cultures for millennia? For indigenous peoples the world is a sacred, interconnected living whole that cares for us and, therefore, we need to revere and care for it. Instead, in our Western culture it has become a “resource” to exploit. The question then is whether we can correct our present imbalance through returning to an awareness of the sacred nature of creation, the Earth, as a living being which needs our love and attention. As I have written previously, “The Earth is not a problem to be solved; it is a living being to which we belong. The Earth is part of our own self and we are part of its suffering wholeness. Until we go to the root of our image of separateness, there can be no healing. And the deepest part of our separateness from creation lies in our forgetfulness of its sacred nature, which is also our own sacred nature.”

Do you see evidence that we are currently up to the task of answering the spiritual and moral questions at the root of our ecological crisis?

The last decades have seen the globalization of our Western materialistic values. Driven by greed and endless desires we have attacked and destroyed the fragile web of life that physically supports us. But we have also created a soulless wasteland that no longer nourishes us with any connection to the sacred nature of creation, a connection that has spiritually sustained humanity for millennia. Thomas Berry, one of the earliest voices to articulate a spiritual ecology, writes, “We are not talking to the rivers, we are not listening to the wind and stars. We have broken the great conversation… all the disasters that are happening now are a consequence of that spiritual ‘autism.’” If we are to cease this destruction and desecration, if we are to no longer pollute the soul as well as the soil, we need to regain a connection to the sacred nature of the Earth. How to reestablish this connection, rejoin this conversation, is a fundamental question we should be asking.

Are we prepared to embrace a new story of life and civilization, one that is radically different to our present story of a consumer-driven culture based upon exploitation and the myth of continual economic progress? Many people today long for such a new story, one that recognizes the Earth as a single interconnected living whole to which we belong. This is a story that nourishes our deeper selves with a sense of connection to the sacred and to the wonder and joy of life that is our heritage.

But collectively we are still caught in the dream, or nightmare, of materialism, which the Earth can no longer support. Indeed it could be argued that the root of the present collective anger, or deep dissatisfaction we are witnessing, comes from a primal knowing that this dream has passed its sell-by date, that its promises of prosperity are empty. And yet because our culture does not ask the right questions, there is no possibility for a real answer.

The ecological issues we face today require solutions urgently. Is telling new stories about our relationship with the Earth really going to bring about the solutions we need right now? What you’re describing strikes me as a slow process.

Although the environmental crisis has accelerated in recent years, it is the result of a mindset that the West has embraced for centuries. And it may take centuries for a new story to unfold.

It can be asserted that our present ecological problems are too dire to be answered by a “new story,” an idealistic vision of recognizing the unity of life and reconnecting to the sacred within creation. And yes, there are critical issues that need to be addressed at the present moment: reducing carbon emissions, the loss of species, acidification of the oceans, and the widespread pollution of our “throw-away culture.” But can science and technology take us to the root of our present predicament, can “greening the economy” be a real answer to ecocide, or do we need a more radical response? Science and technology are born from the reasoning that we are separate from the Earth, a mindset that is at the foundation of a culture where the exploitation of the natural world is now global and catastrophic.

Our present scientific responses may offer valuable short-term fixes, but do not begin to address the deeper issues. What will it take to change our pathological behavior towards our common home? To quote James Gustave Speth, former U.S. Advisor on climate change: “I used to think that top environmental problems were biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse and climate change… I was wrong. The top environmental problems are selfishness, greed, and apathy, and to deal with these we need a cultural and spiritual transformation.”

The first step is to recognize our present predicament and to become aware that materialism is in fact just a story we have been sold, which has us in its grip even as it is destroying our own ecosystem. There is actually no rationale that more “stuff” will make us happy and fulfilled, but rather it appears to have the opposite effect of empty promises that leave us emotionally and spiritually starved. Recognizing the power of stories or myth we come to understand the need for a new story—a story that includes a sustainable relationship to the Earth. Real sustainability does not mean the ability to continue our present energy-intensive consumer-driven culture, but sustainability for all of creation, for the living Earth to which we belong.

But before we can fully articulate—or live—such a new story, we need to reconnect with the sacred nature of creation, rejoin the great conversation that was central to the way of life of our ancestors. This “work that reconnects,” as Joanna Macy calls it, has many forms, but a central theme is empowering the individual, opening our eyes and ears to the mystery and wonder of creation in all of its diversity, and returning each of us to our real place of belonging within life.

Photos courtesy of unsplash.com

Post A Comment:

0 comments: